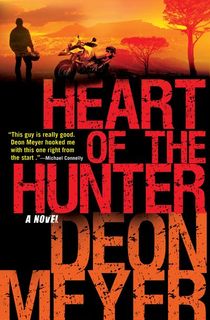

If you’re looking for an epic thriller meets crime fiction adventure, then Deon Meyer’s Heart of the Hunter is your next read—and watch! A book so good it's now been adapted by Netflix.

Gentle giant Tiny Mpayipheli, once a government gun for hire, is begrudgingly sucked back into the industry upon hearing of a trusted old friend’s kidnapping.

Leaving his quiet country life behind, Tiny only has 72 hours to deliver the ransom, but he must evade an army of security forces tasked with getting in his way and a double agent who is too close to powerful domination for comfort. Sitting atop a hijacked motorcycle, Tiny slinks through the African backcountry to save his friend as fast as he can.

According to reviews, both the book and the movie provide an incredible story of post-apartheid South Africa, and Tiny is quick to become a character worth rooting for.

If you’re looking for an action-packed and suspenseful adventure that features South African modern intelligence services and a subtle introduction to South Africa’s political strife, grant Heart of the Hunter a spot on your TBR and Watch Lists.

Read an excerpt from this heart-pounding book—and watch the Netflix trailer down below!

Watch the Heart of the Hunter trailer

Read an excerpt of Heart of the Hunter and then purchase your own copy!

1984

He stood behind the American. Almost pressed against him by the crush of Le Metro. His soul was far away at a place on the Transkei coast where giant waves broke in thunder.

He thought of the rocky point where he could sit and watch the swells approaching in lines over the Indian Ocean, in awe at their journey over the long, lonely distance to hurl and break themselves against the rocks of the Dark Continent.

Between the sets of waves there is a time of perfect silence, seconds of absolute calm. So quiet he can hear the voices of his ancestors—Phalo and Rharhabe, Nquika and Maqoma, the great Xhosa chiefs, his bloodline, source, and refuge. He knew that is where he would go when his time came, when he felt the long blade and the life run out of him. He would return to those moments between the explosions of sound.

He came back to himself slowly, almost carefully. He saw they were only minutes from the St. Michel Metro station. He leaned down, only half a head, to the ear of the American. His lips were close like a lover.

“Do you know where you are going when you die?” he asked in a voice as deep as a cello, the English heavy with an accent of Africa.

The tendons in the back of the enemy’s neck pulled taut, big shoulders tilted forward.

He waited calmly for the man to turn in the overfilled crush of the train. He waited to see the eyes. This is the moment he thirsted for. Confrontation, throwing down the gauntlet. This was his calling, instinctive, fulfilling him. He was a warrior from the plains of Africa, every sinew and muscle knit and woven for this moment. His heart began to race, the sap of war coursed through his blood, he was possessed by the divine madness of battle.

The body turned first, unhurried, then the head, then the eyes. He saw a hawk there, a predator without fear, self-assured, amused even, the corners of the thin lips lifting. Centimeters apart, it was a strange intimacy.

“Do you know?”

Just the eyes staring back.

“Because soon you will be there, Dorffling.” He used the name contemptuously, the final declaration of war that said he knew his enemy, the assignment accepted, the dossier studied and committed to memory.

He saw no reaction in the lazy eyes. The train slowed and stopped at St. Michel. “This is our station,” he said. The American nodded and went, with him just a step behind, up the stairs into the summer night bustle of the Latin Quarter. Then Dorffling took off. Along the Boulevard San Michel toward the Sorbonne. He knew prey chooses familiar territory. Dorffling’s den was there, just around the corner from the Place du Pantheon, his arsenal of blades and garottes and firearms. But he hadn’t expected flight, thought the ego would be too big. His respect deepened for the ex-Marine, now CIA assassin.

His body had reacted instinctively: the dammed-up adrenaline exploding, long legs powering the big body forward rhythmically, ten, twelve strides behind the fugitive. Parisian heads turned. White man pursued by black man. An atavistic fear flared in their eyes.

The American spun off into the Rue des Écoles, right into the Rue St. Jacques, and now they were in the alleys of the university, barren in the August of student holidays, the age-old buildings somber onlookers, the night shadows deep. With long, sure strides he caught up with Dorffling, shouldered him. The American fell silently to the pavement, rolled forward, and stood up in one sinuous movement, ready.

He reached over his shoulder for the assegai in the scabbard that lay snug against his back. Short handle, long blade.

“Mayibuye,” he said softly.

“What fucking language is that?” Hoarse voice without inflection.

“Xhosa,” he said, the click of his tongue echoing sharply off the alley walls. Dorffling moved with confidence, a lifetime of practice in every shift of the feet. Watching, measuring, testing, round and round, the diminishing circles of a rhythmic death dance. Attack, immeasurably fast and before the knee could drive into his belly, his arm was around the American’s neck and the long thin blade through the breastbone. He held him close against his own body as the light blue eyes stared into his.

“Uhm-sing-gelli,” said the Marine.

“Umzingeli.” He nodded, correcting the pronunciation softly, politely. With respect for the process, for the absence of pleading, for the quiet acceptance of death. He saw the life fade from the eyes, the heartbeat slowing, the breaths jerky, then still.

He lowered the body, felt the big, hard muscles of the back soften, laid him gently down.

“Where are you going? Do you know?”

He wiped the assegai on the man’s T-shirt. Slid it slowly back into the scabbard.

Then he turned away.

MARCH

Transcript of interview with Ismail Mohammed by A. J. M. Williams, 17 March, 17:52, South African Police Services offices, Gardens, Cape Town

W: You wanted to talk to someone from Intelligence?

M: Are you?

W: I am, Mr. Mohammed.

M: How do I know that?

W: You take my word for it.

M: That’s not good enough.

W: What would be good enough for you, Mr. Mohammed?

M: Have you got identification?

W: You can check this out if you want to.

M: Department of Defence?

W: Mr. Mohammed, I represent the State Intelligence Service.

M: NIA?

W: No.

M: Secret Service?

W: No.

M: What then?

W: The one that matters.

M: Military Intelligence?

W: There seems to be some misunderstanding, Mr. Mohammed. The message I got was that you are in trouble and you want to improve your position by providing certain information. Is that correct?

[Inaudible]

W: Mr. Mohammed?

M: Yes?

W: Is that correct?

M: Yes.

W: You told the police you would give the information only to someone from the intelligence services?

M: Yes.

W: Well, this is your chance.

M: How do I know they are not listening to us?

W: According to the Criminal Procedures Act, the police must advise you before they may make a recording of an interview.

M: Ha!

W: Mr. Mohammed, do you have something to tell me?

M: I want immunity.

W: Oh?

M: And guaranteed confidentiality.

W: You don’t want Pagad to know you’ve been talking?

M: I am not a member of Pagad.

W: Are you a member of Muslims Against Illegitimate Leaders?

M: Illegal Leaders.

W: Are you a member of MAIL?

M: I want immunity.

W: Are you a member of Qibla?

[Inaudible]

W: I can try to negotiate on your behalf, Mr. Mohammed, but there can be no guarantees. I understand the case against you is airtight. If your information is worth anything, I can’t promise you more than that I do my best. . . .

M: I want a guarantee.

W: Then we must say good-bye, Mr. Mohammed. Good luck in court.

M: Just give me—

W: I’m calling the detectives.

M: Wait . . .

W: Good-bye, Mr. Mohammed.

M: Inkululeko.

W: Sorry?

M: Inkululeko.

W: Inkululeko?

M: He exists.

W: I don’t know what you’re talking about.

M: Then why are you sitting down again?

Featured image: Gustav Schwiering / Unsplash