Raymond Chandler is undoubtedly one of the most recognizable names in crime fiction. The writer pioneered an entirely new style, featuring a complex sleuth who struggles to prevail against a corrupt system. Chandler’s brainchild was Philip Marlowe, the quintessential detective character that came to define the hardboiled style.

Throughout his career, Chandler wrote seven novels and a great deal of short stories. Nearly all of the novels were adapted into successful films, several of them starring Humphrey Bogart in the role of Marlowe. He also succeeded as a screenwriter, co-writing Double Indemnity and Alfred Hitchcock’s Strangers on a Train.

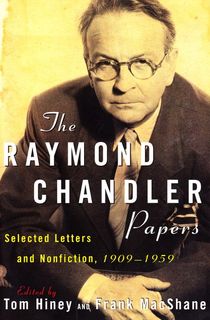

With his lasting influence on the crime fiction genre, Raymond Chandler has become a larger-than-life figure. However, The Raymond Chandler Papers gives readers new access to the author and allows us to delve into his life, from his point of view. The book is largely a collection of letters written by Chandler, interspersed with other nonfiction documents about his life and the thought process behind his work.

Read on for an excerpt from The Raymond Chandler Papers, in which the writer describes how fame and the publishing business are merely distractions to his true passion for writing.

Letter to Dale Warren, publicity director of the Houghton Mifflin publishing firm, 7 January 1945. Chandler's relationship with Alfred Knopf had soured during his time in Hollywood, following a plagiarism incident. It had been brought to the attention of Chandler, by a fan, that the crime writer James Hadley Chase was lifting whole passages of Chandler's old fiction, most blatantly in a book called No Orchids for Miss Blandish. Chandler had contacted both his British and American publishers. While Hamish Hamilton had forced Chase to write an apology in the British trade press, Knopf – under advice from his attorney – had decided not to press the matter. Annoyed, Chandler had moved to Houghton Mifflin. To enhance the fresh slate, he was about to take the opportunity to change agents, leaving Sydney Sanders for the New York firm Brandt & Brandt.

I wrote melodrama because when I looked around me it was the only kind of writing I saw that was relatively honest and yet was not trying to put over somebody's party line. So now there are guys talking about prose and other guys telling me I have a social conscience. P. Marlowe has as much social conscience as a horse. He has a personal conscience, which is an entirely different matter. There are people who think I dwell on the ugly side of life. God help them! If they had any idea how little I have told them about it! P. Marlowe doesn't give a damn who is president; neither do I, because I know he will be a politician. There was even a bird who informed me I could write a good proletarian novel; in my limited world there is no such animal, and if there were, I am the last mind in the world to like it, being by tradition and long study a complete snob. P. Marlowe and I do not despise the upper classes because they take baths and have money; we despise them because they are phony. And so on. And now I see ahead of me either an acute self-consciousness about simple things which I never had any idea of explaining, or a need to explain them at length, and with fury, in the very lingo I had been trying to forget. Because that is the only lingo people who can understand explanations of the sort will accept them in.

I have a letter from a lady in Caracas, Venezuela, who asks me if I would like to be her friend when she comes to New York. It has a faint suggestion about it of another letter I had once from a girl in Seattle who said that she was interested in music and sex, and gave me the impression that, if I was pressed for time, I need not even bother to bring my own pyjamas.

Still from The Big Sleep, starring Humphrey Bogart and Lauren Bacall. The film is based on Raymond Chandler's short story, "Killer in the Rain."

Photo Credit: Warner Bros.Letter to Hamish ‘Jamie’ Hamilton,

Chandler's British publisher, 11 January 1945. Chandler quotes a recent letter from Hamilton, whom he has never met.

‘I gather that he is a very big shot in Hollywood these days, and might resent advice, whoever the sender may be and however good his intentions.’ That really cuts me to the quick. I am not a big shot in Hollywood or anywhere else and have no desire to be. I am, on the contrary, extremely allergic to big shots of all types wherever found, and lose no opportunity to insult them whenever I get the chance. Furthermore, I love advice and if I very seldom take it, on the subject of writing, that is only because I have received practically none except from my agent, Sydney Sanders, and he has rather concentrated on trying to make me write stuff for what we call the slick magazines over here. That is, the big shiny paper national weeklies and monthlies which cater principally to the taste of women. I have always felt myself entirely unfitted for this kind of writing. I much prefer Hollywood, with all its disadvantages.

Why not try me with a little advice some time? I am sure I should treat yours with the greatest respect and should, in any case, like to hear from you.

Letter to Charles Morton,

15 January 1945. Chandler had just signed another contract to work for Paramount, working on an original screenplay. ‘HJ’ is Henry James.

Yes, I know damn well that Harry Fitt was one of the clan of Limerick. I didn't know that he drank, but liquor was a family vice. Those who escaped it either turned religious or went in for white duck pants, like my Uncle Gus. Harry, your father's hired hand, must have been a cousin of my uncle. He was no near relation and I hardly know him, but when I read your letter I recalled that there was a Harry Fitt, that he lived in Omaha and that he worked in a hardware store. Since I was fresh out from England at the time and a hardware store was ‘trade’ I could hardly be expected to get on terms of anything like familiarity with him. Boy! Two stengahs, chop chop!

I am back at the grind and you might as leave write me there for a while. It makes no difference. (Perhaps you won't be writing to me any more at all.) In less than two weeks I wrote an original story of 90 pages like this. All dictated and never looked at until finished. It was an experiment and for a guy subject from early childhood to plot-constipation, it was rather a revelation. Some of the stuff is good, some very much not. But I don't see why the method could not be adapted to novel writing, at least by me. Improvise the story as well as you can, in as much detail or as little as the mood seems to suggest, write dialogue or leave it out, but cover the movement, the characters and bring the thing to life. I begin to realize the great number of stories that are lost by us rather meticulous boys simply because we permit our minds to freeze on the faults rather than let them work for a while without the critical overseer sniping at everything that is not perfect. I can see where a special vice might also come out of this kind of writing; in fact two: the strange delusion that something on paper has a meaning because it is written. (My revered HJ rather went to pieces a bit when he began to dictate.) Also, the tendency to worship production for its own sake. (Gardner suffers badly from this: but God never had any idea of making him a writer anyway. Edgar Wallace ditto. But Dumas Père might really have missed something by grinding the stuff out of the sausage machine.)

Had a nice letter from Dale Warren, but I wish people would stop writing letters about the neglected works of Raymond Chandler. I am so little neglected that I am often actually embarrassed by too much attention.

Letter to Charles Morton,

21 January 1945.

I have one complaint to make, and it is an old one – the cold silence and the stalling that goes on when something comes in that is not right or is not timely. This I resent and always shall. It does not take weeks to tell a man (by pony express) that his piece is wrong when he can be told in a matter of days that it is right. Editors do not make enemies by rejecting manuscripts, but by the way they do it, by the change of atmosphere, the delay, the impersonal note that creeps in. I am a hater of power and of trading, and yet I live in a world where I have to trade brutally and exploit every item of power I may possess. But in dealing with the Atlantic, there is none of this. I do not write for you for money or for prestige, but for love, the strange lingering love of a world wherein men may think in cool subtleties and talk in the language of almost forgotten cultures. I like that world.

Want to keep reading? Download The Raymond Chandler Papers now.

Raymond Chandler’s lively personality and love for writing (but not for the business) shine through in this passage. For more of Chandler’s insights on publishing and the faults of the mystery genre before he came on the scene, download The Raymond Chandler Papers.

This post is sponsored by Open Road Media. Thank you for supporting our partners, who make it possible for Murder & Mayhem to continue publishing the mystery stories you love.

Featured photo of Raymond Chandler: Alchetron