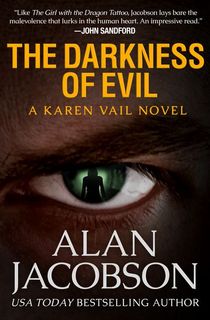

I first met Captain Joe Ramos almost a decade ago while researching the second and third FBI profiler Karen Vail novels, Crush and Velocity, respectively. At the time, Joe was a sergeant in charge of San Diego’s SWAT unit. When I rolled into the downtown police department headquarters complex, I thought I knew the basics of how SWAT operated. But as I would soon learn, I was wrong. With Joe’s tutoring, I built a solid foundation of knowledge that I applied to the scenes I wrote not only for Crush and Velocity, but also for other books to come in the Vail and OPSIG Team Black covert ops series—including my latest release, The Darkness of Evil.

In the SWAT operations center, Joe took me through the various vehicles the team uses for surveillance and operations, showed me their planning manuals, and explained the scenarios they encounter—and how they build a strategy for approaching each armed suspect. On another visit, I accompanied Joe to their training facility, which is furnished with equipment, mock buildings, airplane fuselages, rappelling towers, and various other structures to provide the officers with a solid cross section of the scenarios they’re likely to encounter in the field.

ALAN JACOBSON: Joe, I came away from our meetings incredibly impressed by the degree of preparation SWAT engages in. You guys practice multiple times per week, right?

JOE RAMOS: That’s correct, Alan. Our full-time operators actually train every day. Typically, the team starts at 0600 with a workout emphasizing both strength and endurance. This ensures optimal performance during long training days and lengthy SWAT operations. After the morning workout, which usually concludes at 0800, the team meets for the training session of the day. Training typically focuses on team movements, such as hostage rescue or high-risk warrant service, or firearms training. A variety of situations utilizing role players are regularly presented as challenges during these training sessions. The use of video cameras is a regular component of this training, especially during the debriefing sessions that occur after every repetition.

Additionally, specific training related to specialized duties and capabilities such as explosive breeching, SCUBA operations, specialty munitions, and utilization of robots and technology are also conducted and documented to ensure regulatory compliance and certifications throughout the year.

I have a reputation for doing in-depth research to “get it right” when I compose my scenes. For me, the challenge is that when SWAT enters a structure, the search is methodical and lengthy—which can conflict with my desire to move the story forward briskly (unless the story/novel revolves around law enforcement’s house/building breach). I’ve learned to write the scenes the way I want relative to pacing, then send it to you to mark up anything that I got wrong. I can then adjust as needed—but at least I’ve got the structure down for how I want the scene to unfold.

Well there are many ways to skin a cat, right? Although there are industry standards in the tactical world, different teams have different opinions, and quite frankly different styles regarding team movements and situational choices. Every team must decide on an operational philosophy that suits their team best and then train to that style. I’m sure there are many brain surgeons with different approaches to performing a particular procedure, but that doesn’t make one right and the other wrong, just different.

Authors are the same way. Some swear by outlining their story, while others are passionate that outlining kills creativity. But one of the things about writing a novel is that there are good practice guidelines, but no true rules. If it works, it works. An example is The Martian. Andy Weir does exactly what we’re not supposed to do: the novel is chock full of long, dense, technical explanations of technology and science. But Weir does it so well, and with humor—and it works.

This model doesn’t work in your world, where training and procedures dominate, where every member of the team must know what his or her colleague is going to do in a given situation—or people could die. And therein lies my conundrum in story pacing vs. adhering to SWAT protocols. In The Darkness of Evil, we had an exciting scene unfolding with a well-armed, barricaded suspect. But when done properly, the search of a building can be painstakingly slow, and the last thing I wanted to do is disrupt its internal rhythm by having the tactical team perform a methodical three-hour search.

That’s right, Alan. Most teams have adopted a philosophy of “slow and methodical” searching when the problem is a barricaded suspect refusing to surrender or attempting to elude capture. In these cases, there’s no reason to compromise safety by using a faster, more aggressive searching technique. Conversely, when performing a hostage rescue, the more aggressive technique is a much more common choice as there may be a need for speed, surprise, aggression and diversion to overcome the opposition. So in many respects it is not a one-size-fits-all business.

If you recall, in one of our earlier discussions several years ago, I helped you with scenes for Velocity. You had the SWAT Team in San Diego utilizing hostage rescue tactics when entering a structure looking for a barricaded suspect. We discussed how the San Diego SWAT Team would most likely not have opted for the aggressive technique—even though it is much more fun and exciting for your readers. Truth be told, it is much more exciting for our operators too, but not the right call for our team.

I attended numerous tactical team leader conferences and courses during my 19-year SWAT assignment. I can tell you that there are some teams who will opt for more aggressive tactics in situations while other teams may use a more methodical approach. As I mentioned earlier, many ways to skin a cat. When I’m working with you on a scene, like the ones in The Darkness of Evil, I correct the procedural things you missed, I make sure your terminology is correct and that the equipment used in the scene is proper. On occasion, I also suggest alternate methods of approaching a scenario to give you a choice and some flexibility in telling your story.

Author Alan Jacobson (left) and Captain Joe Ramos.

Photo Credit: Alan JacobsonWant to know more about your favorite thriller books? Sign up for Murder & Mayhem's newsletter and get suspenseful stories delivered straight to your inbox.

You also add details that I can include at my option—which I almost always do include! Such details sometimes give me other ideas I can create around. I want to go back to your preparation for a moment. During my SWAT visits, one thing that surprised me most was how detailed your advance planning is. I always thought most SWAT deployments were last minute operations. But if the case permits, your team performs a variety of reconnaissance activities that can take days.

We refer to these as planned operations vs. emergency call outs. Typically, a planned operation will provide at least a day or two to prepare, and in many cases several days or weeks. Regardless of the amount of time, we strive to consistently include a variety of pre-event preparations and protocols.

Typically, we’ll utilize air resources to photograph the target location and surrounding areas. These photographs are part of the operation briefing and will pinpoint exact locations for positioning of operators during the operation as well as contingency locations for any unexpected circumstances during the execution of the mission. We may drive by the location in an undercover vehicle to obtain street level video footage. Photos and videos are then studied by the mission planners to identify structural and environmental challenges such as locked gates, security bars, large dogs, surveillance cameras, etc.

What may be surprising to you is the creativeness of the SWAT officers during the intel gathering period. As an example, officers will visit real estate websites and obtain photos of the target location from past listings. I recall one instance where we were provided a virtual tour of a high-risk warrant service narcotic location from a real estate website.

Once an initial plan is prepared, several team meetings are held to refine the plan and discuss strategies. Eventually an overall plan is produced and presented to the SWAT command staff for approval.

On the day of the mission, a comprehensive briefing is conducted with all of the tactical officers and investigators. This briefing ensures we are providing the proper response and adhering to all legal issues including the terms of the search and/or arrest warrant(s). To the extent possible, the target location is recreated in our parking lot and several walkthroughs are conducted to prepare the team. A final opportunity is given for questions and clarifications. The team is then organized in a convoy to facilitate the planned order of arrival at the target location.

Usually there are “eyes on” the target by investigators, who give real time updates on the activity in and around the location to the team while they travel to the site. After the mission is completed and the scene, including detained or arrested suspect(s), is turned over to investigators, the SWAT team returns to their training facility where an extensive debriefing is conducted to discuss all aspects of the operation, good and bad.

What happens when you don’t have the time to prepare? Let’s say it’s an unstable hostage situation. How does that op differ for you and the officers? How does the immediacy impact your level of success?

As we discussed earlier, the SWAT Team invests hundreds of hours every year training. Much of that training is focused on responding to unstable situations. An officer shot, a robbery gone bad, a family disturbance, etc. can all lead to an unstable situation including a hostage problem. All SWAT officers know that an immediate rescue attempt may be called for at any moment during a hostage problem. We count on the SWAT officers at the scene to make very quick assessments. If there is time to gather more resources, including additional officers, our odds of success are greatly increased. Having said that, we also recognize that if a citizen or victim’s life is in jeopardy, we may not have that luxury—which is why we train for all possible responses, including immediate deployment. The last thing officers want to do is wait for additional resources while innocent victims are harmed or killed. Therefore, all officers have the approval to act with the appropriate use of force just as they would in any confrontation with a suspect during the course of their duties. We train our officers to recognize the situation when action needs to be taken immediately and allow them to take that action when lives are at stake.

What was the toughest case you ever had to prepare for?

Over the course of my career we have served hundreds of high risk warrants, conducted dozens of surveillances, protected numerous presidents and other dignitaries as well as responded to and rescued hostages during very volatile situations. None of these are as tough as responding to a downed officer. I have personally responded as the SWAT Commander to the shooting and murder of fellow officers. Twice, I’ve had to advise SWAT team members that a fellow officer did not survive. Despite this devastating information, team members go about their business professionally and with a sense of pride and purpose that I will never forget and always treasure.

Thanks Joe. You’re one of the gems in law enforcement, and San Diego PD is fortunate to have you, your training, experience, and guidance. I know your time is tight, so on behalf of my readers I’d like to thank you for your service—and your assistance in helping me keep it real.

You're welcome, Alan.

Want to know more about your favorite thriller books? Sign up for Murder & Mayhem's newsletter and get suspenseful stories delivered straight to your inbox.