For Agatha Christie, the discovery of the tomb of King Tutankhamun 100 years ago this month would spark a lifelong fascination with archaeology. Her interest in the ancient world would bring her inspiration, joy, and love.

In mystery fiction digging up the past is often necessary to solve a crime, but for the great mystery writer Agatha Christie, literally digging up the past was also a hobby and a passion. Her interest in archaeological excavations had been peaked by Howard Carter’s unearthing of the tomb of the Egyptian boy-king Tutankhamun in November 1922, a discovery that created a worldwide craze for Ancient Egypt. While that fad quickly fizzled out, Christie’s commitment to the Ancient World would last until her final days. It would transform her life and bring her lasting happiness.

Agatha Christie

Photo Credit: Agatha ChristieFollowing her husband Archie’s request for a divorce in 1926, the Queen of Crime had lived a miserable existence. The discovery of her husband’s love for his golfing partner Nancy Neele had sparked her mysterious 11-day disappearance and then a bout of depression. She would characterize the following years as a time of “sorrow, despair, and heartbreak”.

The alleged Abraham house in Ur city, Dhi Qar, southern Iraq

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons Public DomainTo try and shake herself free of the darkness, in 1929 Christie took a trip on The Orient Express from Paris to Istanbul. A chance conversation over dinner as the great train rumbled across Italy, lead her to extend the trip to Baghdad. From the Iraqi capital, she traveled to see the remains of the great Sumer city of Ur—one of the world’s earliest civilizations. Here she became friends with the managers of the site, Leonard and Kathleen Woolley.

The ziggurat of Kish, Tell al-Uhaymir, Mesopotamia, Iraq

Photo Credit: Wikimedia Commons Public DomainThe archaeologists invited the author to return the following year. When she did, Christie found herself being guided around the great Babylonian ziggurat and royal tomb by a young man named Max Mallowan. The Oxford-educated Londoner was twenty-five, thirteen years Christie’s junior. Up to that point, he’d seemed more interested in Mesopotamian pottery fragments than in living human beings, but something about the author set his heart fluttering. Luckily she felt the same way about him. Within a year they were married and living together in a house in Chelsea, London. It was a romantic relationship that would last until Christie’s death in 1976.

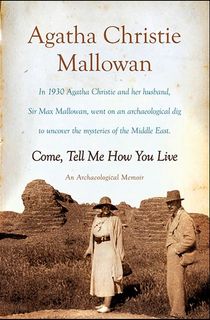

Max was gallant, intelligent, and tough (he’d serve as an RAF pilot in World War Two despite being over forty) and would be knighted for his services to archaeology by Queen Elizabeth II. Christie would show similar qualities of durability and acuity, accompanying her husband on dozens of digs in the deserts of the Middle East, sleeping in tents, and living off tinned food in remote corners where a warm shower was a distant dream. She loved every minute of it—the thrill of discovery, the camaraderie amongst the teams of experts and helpers, the laughter around the campfire after a long day in the dirt. She’d document those early years with Max in Come Tell Me How You Live (1946), a humorous and engaging book that mixes memoir with an evocative travelogue.

Come, Tell Me How You Live

Christie’s travels and experiences with Max also provided inspiration for her work, Beginning with Murder in Mesopotamia in 1936 she’d write a number of mysteries in which archaeological sites form the setting, while her travels to visit the great wonders of the ancient world would also provide details for novels such as the classic Hercule Poirot mystery Death on the Nile (1937) and the 1954 spy story Destination Unknown (which takes place in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco).

Murder in Mesopotamia

Death on the Nile

It was not only the places that featured in Christie’s mysteries but also the characters she met on the digs. Several real archaeologists turn up, craftily disguised, in Murder in Mesopotamia (based on excavations Christie and Mallowan worked on in Chagar Bazar and Ur) and Appointment with Death (1938). The latter novel—set in Petra in what is now Jordan—is dedicated to “My many archaeological friends in Iraq and Syria”, though a few of those friends were reportedly a little irritated to find themselves featuring in a murder investigations led by Hercule Poirot (The little Belgian sleuth is helpfully on hand in the Middle East for both mysteries, in the first wrapping up a case in Syria and the second enjoying a short holiday in Jerusalem). A later spy thriller, They Came to Baghdad (1951) sees archaeology used as a front for international espionage and features a number of Iraqi sites Christie and Mallowan visited together.

Appointment with Death

The Ancient World would also be the setting for Christie’s only foray into the sub-genre of historical detective fiction. Death Comes as the End (1945) is a dark tale of familial jealousy that takes place in the Ancient Egyptian city of Thebes around 2000 BC. It features a wealthy farmer and his potentially murderous new concubine. Death Comes as the End was written with the help of the couple’s close friend, the renowned Egyptologist, Stephen Glanville. Glanville would also provide background for arguably Christie’s least known work, Akhnaton, a seldom performed play (written in 1937 it wasn’t published until 1973) which features the boy king Tutankhamun.

Death Comes as the End

Fascinated by the buildings, artifacts, and history of Sumer, Elam, and other kingdoms that formed the cradle of civilization, Christie would continue visiting excavations and ancient sites with her husband until well into her sixties. Her enthusiasm for archaeology—the science that had brought her so much happiness—would never wane.