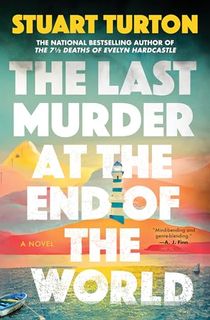

You know that when the reviews say a book is “even better than The 71/2 Deaths of Evelyn Hardcastle'' you’ve got a real winner on your hands.

Stuart Turton’s specialties lie in mixing locked-room mysteries with a literary fiction, sci-fi, fantasy, and horror combo (which is quite the mouthful, but works every time).

And his newest release, The Last Murder at the End of the World, is absolutely no different.

It gives that same locked-room mystery ambiance meets sci-fi with a dash of lit fiction and underlying horrific motifs that The Hunger Games dealt with—though this book is much heavier on the mystery.

In it, there are 122 villagers and three scientists trapped on an island due to the fatal fog that has swallowed the rest of the world.

They’ve learned to live harmoniously together; fishing, farming, feasting, and obeying their nightly curfew, as set up for everyone by the scientists.

Until one day, one of the beloved scientists is found stabbed to death. And the murder has messed with the security system that keeps the fog off the island.

If they can’t solve the murder in the next 107 hours, the fog will kill them all.

But even worse: the security system has also wiped everyone’s memories of exactly what happened the night before, meaning that not only does no one know the culprit is, but the culprit themself doesn’t even know it.

Intrigued? So are we. Read the excerpt to curb your curiosity before you can get your hands on it on May 20th.

Read on for an excerpt of The Last Murder at the End of the World, and then purchase the book.

Prologue

“Is there no other way?” asks a horrified Niema Mandripilias, speaking out loud in an empty room.

She has olive skin and a smudge of ink on her small nose. Her gray hair is shoulder length, and her eyes are strikingly blue with flecks of green. She looks to be around fifty and has for the last forty years. She’s hunched over her desk, lit by a solitary candle. There’s a pen in her trembling hand and a confession beneath it that she’s been trying to finish for the last hour.

“None that I can see,” I reply in her thoughts. “Somebody has to die for this plan to work.”

Suddenly short of air, Niema scrapes her chair back and darts across the room, swiping aside the tattered sheet that serves as a makeshift door before stepping into the muggy night air.

It’s pitch-black outside, the moon mobbed by storm clouds. Rain is pummeling the shrouded village, filling her nostrils with the scent of wet earth and cypress trees. She can just about see the tops of the encircling walls, etched in silver moonlight. Somewhere in the darkness, she can hear the distant squeal of machinery and the synchronized drumbeat of footsteps.

She stands there, letting the warm rain soak her hair and dress. “I knew there’d be a cost,” she says, her voice numb. “I didn’t realize it would be so high.”

“There’s still time to put this plan aside,” I say. “Leave your secrets buried, and let everybody go about their lives as they’ve always done. Nobody has to die.”

“And nothing will change,” she shoots back angrily. “I’ve spent ninety years trying to rid humanity of its selfishness, greed, and impulse toward violence. Finally, I have a way to do it.” She touches the tarnished cross hanging around her neck for comfort. “If this plan works, we’ll create a world without suffering. For the first time in our history, there’ll be perfect equality. I can’t turn my back on that because I don’t have the strength to do what’s necessary."

Niema speaks as if her dreams were fish swimming willingly into her net, but these are murky waters, far more dangerous than she can see.

From my vantage in her mind—and the minds of everybody on the island—I can predict the future with a high degree of accuracy. It’s a confluence of probability and psychology, which is easy to chart when you have access to everybody’s thoughts.

Streaking away from this moment are dozens of possible futures, each waiting to be conjured into existence by a random event, an idle phrase, a miscommunication, or an overheard conversation.

Unless a violin performance goes flawlessly, a knife will be rammed into Niema’s stomach. If the wrong person steps through a long-closed door, a huge, scarred man will be emptied of every memory, and a young woman who isn’t young at all will run willingly to her own death. If these things don’t happen, the last island on earth will end up covered in fog, everything dead in the gloom.

“We can avoid those pitfalls if we’re cautious,” says Niema, watching lightning tear through the sky.

“You don’t have time to be cautious,” I insist. “Once you commit to this plan, secrets will surface, old grudges will come to light, and people you love will realize the extent of your betrayal. If any of these things disrupts your plan, the human race will be rendered extinct in one hundred and seven hours.”

Niema’s heart jolts, her pulse quickening. Her thoughts waver, only to harden again as her arrogance takes the reins.

“The greatest achievements have always brought the greatest risk,” she says stubbornly, watching a line of figures walking stiffly in the darkness. “Start your countdown, Abi. In four days, we’re either going to change the world or die trying.”

107 Hours until Humanity’s Extinction

1

Two rowboats float at world’s end, a rope pulled taut between them. There are three children in each with exercise books and pencils, listening to Niema deliver her lesson.

She’s at the bow of the boat on the right, gesticulating toward a wall of black fog that rises a mile into the air from the ocean’s surface. The setting sun is diffused through the sooty darkness, creating the illusion of flames burning on the water.

Thousands of insects are swirling inside, glowing gently.

“They’re held back by a barrier produced by twenty-three emitters located around the island’s perimeter…”

Niema’s lesson wafts past Seth, who’s the only person in either of the boats not paying attention. Unlike the children, who range in age from eight to twelve, Seth’s forty-nine, with a creased face and sunken eyes. It’s his job to row Niema and her students out here and back again when they’re done.

He’s peering over the edge, his fingers in the water. The ocean’s warm and clear, but it won’t stay that way. It’s October, a month of uncertain temper. Glorious sunshine gives way to sudden storms, which burn themselves out quickly, then apologize as they hurry away, leaving bright-blue skies in their wake.

“The emitters were designed to run for hundreds of years unless…” Niema falters, losing her thread.

Seth looks toward the bow to find her staring into space. She’s given this same lesson every year since he was a boy, and he’s never once heard her trip over the wording.

Something has to be wrong. She’s been like this all day: seeing through people, only half listening. It’s not like her.

A swell brings a dead fish floating by Seth’s hand, its body torn to shreds, its eyes white. More follow, thudding into the hull one after another. There are dozens of them, equally torn apart, drifting out of the black fog. Their cold scales brush against his skin, and he snatches his hand back inside the boat.

“As you can see, the fog kills anything it touches,” Niema tells her students, gesturing to the fish. “Unfortunately, it covers the entire earth, except for our island and half a mile of ocean surrounding it.”

2

Magdalene’s sitting cross-legged at the end of a long concrete pier that extends into the glittering bay. Her hair is a tangled red pile, clumsily tied up with a torn piece of yellow linen. She looks like some ancient figurehead fallen off her galleon.

It’s early evening, and the bay is filled with swimmers doing laps or else hurling themselves off the rocks to her left, their laughter chasing them into the water.

Magdalene’s staring at the distant rowboats with the children in them, a few flicks of charcoal adding them to the sketchbook in her lap. They seem so small against the wall of black.

She shudders.

Her eleven-year-old son, Sherko, is in one of those boats. She’s never understood why Niema insists on taking them all the way to world’s end for this lesson. Surely, they could learn about their history without being in touching distance of it.

She remembers being out there when she was a girl, hearing this same lesson from the same teacher. She cried the entire way and nearly jumped out to swim for home when they dropped anchor.

“The children are safe with Niema,” I say reassuringly.

Magdalene shivers. She thought sketching this moment would alleviate her worry, but she can’t watch any longer. She was only given her son three years ago, and she still mistakes him for fragile.

“What’s the time, Abi?”

“5:43 p.m.”

She notes it in the corner, alongside the date, jabbing a pin in history, which flutters and rustles on the page.

After blowing away the charcoal dust, she stands and turns for the village. It was formerly a naval base, and from this vantage, it appears much more inhospitable than it actually is. The buildings inside are protected by a high wall, which is covered in ancient graffiti, weeds sprouting from long cracks. Vaulted roofs peek over the top, their gutters hanging loose, the solar panels made into glinting mirrors by the bright sunlight.

Magdalene follows a paved road through a rusted iron gate, the sentry towers so overrun by vegetation they look like hedges.

The barracks looms up in front of her. It’s n-shaped and four stories high, made of crumbling concrete blocks, every inch painted with jungle, flowers, and birds, animals stalking through the undergrowth. It’s a fantasy land, the paradise of people who’ve grown up surrounded by dry earth and barren rock.

Rickety staircases and rusted balconies grant access to the dormitories inside, none of which have doors or windows in the frames. A few villagers are hanging their washing over the railings or sitting on the steps, trying to catch whatever scraps of breeze dare to clamber over the wall. Friends call to her cheerfully, but she’s too anxious to respond.

“Where’s Emory?” she asks, her eyes moving fretfully across the faces in front of her.

“Near the kitchen, with her grandfather.”

Magdalene heads into the space between the two wings of the barracks, searching for her best friend. This used to be an exercise yard for the troops, but it’s slowly been transformed into a park by three generations of villagers.

Flowers have been planted in long beds along the walls, and the old collapsed radar dish has been patched up and turned into a huge bird bath. Four rusted jeeps serve as potters for herbs, while lemon and orange trees grow out of shell casings. There’s a covered stage for musical performances and an outdoor kitchen with six long tables for communal meals. Everybody eats together every night.

One hundred and twenty-two people live in the village, and most of them are in this yard. Games are being played, instruments practiced, and poems written. Performances are being rehearsed on the stage. Food is being cooked and new dishes attempted.

There’s a lot of laughter.

For a second, this joy loosens Magdalene’s worry. She scans the area, searching for Emory, who isn’t hard to find. Most of the villagers are squat and broad-shouldered, but Emory’s slighter and shorter than most, with oval eyes and a huge head of curly brown hair. She once described herself as looking like some strange species of dandelion.

“Stay still,” demands Matis, peering around the statue. “I’m almost finished.”

Matis is nearly sixty, which makes him the oldest man in the village. He’s thick-armed, with gray whiskers and bushy eyebrows.

“I’m itchy,” complains Emory, struggling to reach a spot on her upper back.

“I gave you a break half an hour ago.”

“For fifteen minutes!” she exclaims. “I’ve been standing here with this stupid apple for six hours.”

“Art always has a price,” he says loftily.

Emory sticks her tongue out at him, then resumes her pose, lifting the gleaming apple into the air.

Muttering, Matis returns to his work, shaving a sliver from the sculpture’s chin. He’s so close to it, his nose is almost touching the stone. His eyesight has been fading for the last decade, but there’s nothing we can do. Even if we could, there’d be little point. He’ll be dead tomorrow.

.png?w=3840)