In the equatorial heat of a July morning in Harlem, a middle-aged lady in thigh-high plastic boots was standing underneath the el tracks as our van passed.

“Yo Blauner, tell her the bus don’t stop here.”

It was the summer of 1988. Urban America was melting down. New York City would have a record-breaking 1,896 homicides by the end of the year. A few months earlier, a rookie cop named Edward Byrne had been assassinated by drug dealers in Queens while guarding witness’s house. A friend of a friend died after getting kicked in the neck outside a bar on the Upper West Side. AIDS, homelessness, and racial violence were rampant. The night before, Jesse Jackson had given a speech at the Democratic Convention, imploring the underdogs of society to “keep hope alive.” It sounded a little desperate.

I was stuffed inside the van with six probation officers, going out early to serve warrants and pick up “absconders” who’d failed to show up for their appointments. I’d left my job as a reporter and signed up as a volunteer with probation, because I wanted to write a novel about the times and I needed a close and unusual angle on them.

Related: 7 Neil Cross Books for Fans of Gritty Crime Fiction

I’d been researching the book for several months by then, getting through training, sitting in on “client sessions,” and going on home visits with the Field Service Unit in their bulletproof vests. I’d been in crack dens, homeless shelters, and yes, the occasional middle-class apartment building where affluent-looking lawbreakers lived. I’d seen addiction, despair, rage, and absurdity, but what I wasn’t seeing yet was a coherent story.

“Who’s this first guy we’re picking up?” asked the head of the unit, puffing a cigar in the van’s front seat. “Cedric something, right? What’s his claim to fame?”

“Nothing,” said a female officer with the case file, sitting behind him, a tall woman with a look of exhausted kindness.

“Nothing?” The supervisor raised his eyebrows. “Officer, are you telling me that we are about to arrest an innocent person?”

The female officer took a long time before answering.

“There are no innocent people.”

It was the best laugh we had that summer.

Then the woman with the case file turned to me.

“You know, you start off doing this type of work because you want to help people,” she said. “But after a while, when you’ve given it your best, and they don’t change, you begin to hate them. And you realize that they’re changing you.”

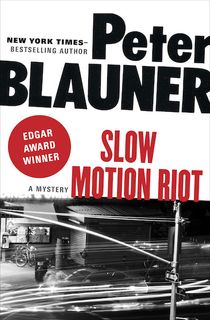

And just like that, I knew what my novel was going to be about. Three years later, it came out. It was called Slow Motion Riot. Some people loved it and gave it accolades. Some people hated it and called me names.

Related: What Do You Do When the Evidence Is Stacked Against You?

Smash-cut to 26 years later. I’m a few blocks from where the lady in thigh-high boots was standing, outside a grimy auto body shop on 114th Street near Morningside Avenue. Instead of probation officers, there’s a television crew taking over the block, shooting an episode of Law & Order: SVU. There are cameramen, make-up ladies, costumers, gaffers, grips, sound people, Teamsters, background actors, and dozens of others working to support the illusion in the mid-December chill. I sit in front of a monitor in the “video village” on the sidewalk, watching Ice-T glower at a pitbull with a Hannibal Lecter-style muzzle on its face while another actor holding the leash pleads, “Walk with us. Spartacus is the only thing that keeps me calm now.”

“Cut.” A few yards away, the director walks out from behind the camera wearing a knit cap with upturned ears. Across the street, a bunch of Harlem kids have recognized her.

“It’s Olivia! Oh damn! That’s Detective Benson. She the director too?”

As the Talking Heads asked long ago: How did I get here?

Well, that’s a long story. Buy me a drink sometime and I’ll tell you. Suffice to say that a lot can change in 26 years. If you told me when I was crawling around crack houses for Slow Motion Riot that someday I’d not only be working with dozens of people on a network TV show but actually enjoying it, I might have accused you of being on the pipe yourself.

When I wrote that book, it was not the stuff of prime-time entertainment and it wasn’t supposed to be. I followed my characters wherever they wanted to go, and didn’t impose any commercial considerations. At one point I might have an idea about a conventional happy ending, but at the last-minute the characters crashed through it and kept going all the way into darkness.

If the novel didn’t work, no one else was to blame. No network executive, producer or actors changed its tone or purpose.

Related: No Beast So Fierce: The Book That Got a Man Released from Prison

Collaboration was not something I was instinctively drawn to. In fact, I associated the word with Vichy government and corporate “team-building exercises.” It seemed like the greater the number of parts, the less the sum. What I liked about writing novels on my own was having the freedom to focus on unexpected and sometimes inexplicable parts of human nature without having to justify those choices to anyone else.

So I had a steep learning when I started writing for television.

Even on programs where there is a showrunner with a strong personality and style, the execution is dependent on production designers, costumers, actors, editors, directors, and the others. All those hands, to some degree, leave fingerprints. Also, most television police procedurals aren’t meant to be provocative individual statements. They’re supposed to provide a sense of comfort and reassurance (though SVU has more than its share of disquieting moments). That may be a good part of the reason why even a failing show on a cable network can have an audience that’s about ten times bigger than the readership of a commercially successful novel.

So why bother writing novels at all?

The answer is probably the same for some writers as it is for drug addicts and serial killers: compulsion. You can’t help yourself. Once you’ve had a taste of saying exactly what you want to say exactly the way you want to say it, you’re already on the road to perdition. Once someone else responds, there’s no turning back. There’s no substitute for the charge that results from being able to communicate directly from the little box in the writer’s head to the little box in the reader’s head.

But once in a while, something comes close. Toward the end of shooting the episode “Padre Sandunguero” for SVU, eight of us found ourselves cramped into a hot little dungeon-like room, all staring at the monitors and wondering why the scene we were watching wasn’t working.

Related: Keep Him Alive for One More Night: The Chilling Story of Q

The script had been rewritten. The actors had rehearsed. The set had been expertly lit and make-up artfully applied. Camera movements had been choreographed. This should have been the penultimate moment, a final confrontation between two lifelong antagonists. But somehow the thing refused to coalesce. A noisy plane overhead ruined the sound on one take. Bodies lurched out of frame on crucial lines. Our day was running out. The director, Mariska Hargitay, also the star of the show, spoke to the actors and called for action one more time. The cameras rolled. We watched the actors say their lines and hit their marks like we were watching a penguin run toward a precipice flapping its wings. And then our guest star suddenly reached out, grabbed his enemy’s face, kissed it and strode out of frame.

It was totally unscripted, possibly insane–and absolutely perfect. Our improbable bird had taken flight, from the nest we’d collectively built. I turned and looked at Mariska, and then at the showrunner and episode’s co-writer, Warren Leight, sitting behind me. Right. Exactly what we had in mind.

All photos via Michael Parmelee / NBC