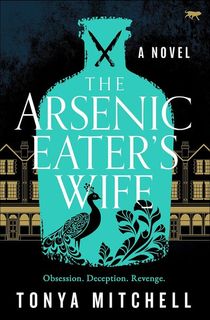

Tonya Mitchell, the critically acclaimed, award-winning author of Feigned Madness comes to us with another “vivid, enthralling, knockout Victorian history.” You know when someone mentions that their influences are made up of the likes of Emily Brontë, Edgar Allen Poe, Mary Shelley, Margaret Atwood, and Agatha Christie, they’re going to write a Gothic like no other.

A modern Gothic inspired by a not-so-modern true story, The Arsenic Eater’s Wife is a dark, atmospheric tale of a woman accused of killing her husband by poisoning him with arsenic.

Like many seemingly idyllic marriages in 1889 Liverpool, England, sinister secrets and webs of lies are revealed as the Sullivan’s marriage crumbles; and like in many seemingly idyllic English towns at the time, the line between guilt and innocence is always blurry. No one knows who to believe.

Constance Sullivan—26-year-old wife of the deceased William Sullivan’s—is brought to trial under the charge of poisoning her husband. Her mother is the only one who believes she's innocent—and the only one fighting to help her prove it.

But one after the other, witnesses emerge with incriminating facts and testimonies about the dark underbelly of their marriage, and Constance looks guiltier after every account.

What these people don’t know is that William himself was purposely taking arsenic. And that the way he treated her would make all these people think twice about wanting to see her hanged.

Constance's accusers believe that because she purchased arsenic, she must be the one who poisoned him. But everyone’s betrayal in the face of the trial is only the beginning—because Constance won’t rest until she has her revenge.

This is not just an “unputdownable”, historical fiction mystery brimming with impeccable research, an atmospheric tone, and believable characters.

It is also a story about reclamation and the convoluted ideas of what it means to be human. Not to mention the complexity of the human heart.

In your race to the final page, Mitchell’s carefully plotted tale will keep you pondering whether Constance is guilty until the very end.

Praise for The Arsenic Eater's Wife

But in the words of LeVar Burton, don’t just take our word for it; here's what early readers are saying:

“Impeccably researched and rich with historical detail, The Arsenic Eater’s Wife is a fictional mystery based on the true story of a woman wrongly convicted of her husband's murder. With more than a hint of the Gothic, Tonya Mitchell masterfully builds a palpable sense of dread throughout, but manages also to offer her characters grace even when their actions and feelings are deeply flawed. This is historical fiction at its best, offering justice in the form of story to a real woman who did not receive her due in life.” —Molly Greeley, author of Marvelous

“Tonya Mitchell’s The Arsenic Eater’s Wife renders a dark and intricately brushed portrait of the dichotomous business of human nature. Set against the scintillating murk of 19th Century Liverpool England, Mitchell’s novel simmers good, and hot, and glorious with atmosphere, arsenic, intrigue, and lies.” —Robert Gwaltney, award-winning author of The Cicada Tree and Georgia Author of the Year

"A gorgeously Gothic and atmospheric whodunit filled with surprising twists and memorable characters that I tore through in a single sitting. Inspired by a true-life crime, The Arsenic Eater’s Wife offers proof that the darkest mystery remains the human heart." —Kris Waldherr, author of Unnatural Creatures: A Novel of the Frankenstein Women and The Lost History of Dreams

And if you’d like to try a sample of this poisonous tale, read an excerpt of The Arsenic Eater’s Wife below.

Read this excerpt of The Arsenic Eater's Wife—and then purchase your own copy to keep reading!

Chapter 1

Torrence House

Liverpool, England

May 18, 1889

The day they come for her, Constance Sullivan is lying still on the bed. She opens her eyes to a dim room with shuttered windows. Ribbons of light reach through the slats, fingering the burled wood of the dresser, the rough brick of the fireplace, the burgundy fleurs-de-lis of the wallpaper. The spare bedroom, not her own. The wrongness of it—that she should be lying here—confounds her, but only for an instant.

Jarring pain knocks at her temple, and then she remembers: William is dead.

She sits up and gulps air. If you go back to sleep you needn’t face it, a voice inside her says, but the absurdity that these last few days can be avoided, slept away, is too much.

Memories split open: Edward’s grip on her upper arms as he shook her; Ingrid’s sly grin as she handed Constance’s note to the police; little Billy’s lips, white and puckered, as he looked down at his father lying prone. “Must he go to the angels, Mummy? Can’t he stay here with us?”

Constance had been too overcome to speak. William might still have been breathing, but he was already gone. Death had crouched in the bedroom for days, its cloven hoofs creeping ever closer.

A whiff of sour air—putrid breath and body odor. Her own. Vomit has congealed in the bedpan on the floor. How many days have they shut her away?

She feels it then, the scrutiny of the air, the leaded weight of it: the house waiting for her next move. It is malevolent, Torrence House. She’d known it the first time she’d stepped across its threshold and felt it taking her in, appraising her weaknesses, testing her senses. She’d shivered and walked its empty rooms, listened to William prattle on about what they could make it when she knew full well the decrepit house had already made itself: its murky cells of rooms, its long corridors that fled into darkness. It was unchangeable, shrouded in a perpetual gloom that no amount of money spent on lavish decor could lift. That day they’d stirred the dust in the front hall into eddies as they left to explore the grounds, and her throat had constricted when William saw the orchard, the hothouse, the pond. “We must have it,” he’d said, and she knew she had lost.

A floorboard moans outside the door. She comes to herself and stands. The contents of the room pitch, and she sags against the bed. She brings up a hand to smooth her hair and winces. Her body feels as if it’s been wrung through a mangle. In all her twenty-six years, she’s never felt so bone-weary. So used up. Her head has just hit the pillow when the door is thrown open. Dr. Hendrickson strides in. He finds her wrist among the bedclothes and doesn’t meet her eyes.

“I—”

“Be still,” he says, his thumb on her pulse. His lips are a scowl. The smell of carbolic soap wafts off him.

She’s about to speak again when Nurse Hawker enters the room and casts the shutters wide. Daylight splashes into the room. Constance feels as if she might be sick.

Male voices downstairs. She has no idea who is in the house.

The thoughts in her head are too crowded, wrestling for space. There’s too much to take in, too much to remember.

A shadow at the threshold. Ingrid, clothed in full mourning. As if she is the widow. For a moment, their eyes catch and hold.

Footsteps on the stairs. The men are coming up.

“You must let me go too,” Constance’s mother shouts from below. “You cannot keep me from her!”

Dr. Hendrickson steps away from the bed, as if his proximity to her will taint him. Nurse Hawker sniffs at Constance before she looks to the doorway.

A policeman is the first to enter. Constance doesn’t stir for fear of vomiting, yet panic shoots through her, swift and stinging. Following him is the superintendent of police. He came before—two days ago, four? She can’t recall his name, what he told her. She’d been too exhausted to listen.

Her solicitor, Mr. Seaver, enters but doesn’t meet her gaze. A fourth man, with heavy jowls and gray whiskers, is next. His eyes dart to her and away. She almost misses Dr. Hendrickson’s deferential nod in his direction, his murmur of “magistrate.”

The superintendent positions himself at the foot of the bed. He still wears his bowler. “This is Mrs. Sullivan, wife of the late William Sullivan,” he calls out, as if on stage. “I understand Mr. Seaver has requested a delay and therefore I need not give evidence.”

“That is correct,” Mr. Seaver says. “I appear for the prisoner and suggest a remand of eight days.”

Prisoner. The room sways and the house waits. Constance’s heartbeat thrashes in her ears. She clutches her stomach, swallows down bile. Vomit has dried in the folds of her dress. There is a bruise on her finger where her wedding ring used to be.

“Eight days?” the magistrate inquires. He can’t bring himself to look at her.

“Mrs. Sullivan is ill,” Seaver says, gesturing to the bed. “She must get her footing. She is in accord with the delay.”

Constance can’t remember when she’d last seen Seaver. Has she, in the days she’s passed ill in this room, agreed to any such thing?

The magistrate nods. “Very well; I consent to a delay in the proceedings.”

The men shuffle out, requiring nothing of her. Downstairs her mother’s voice is shrill, her words so rushed Constance can’t make out their meaning.

Nurse Hawker shuts the door and approaches the bed. “Get dressed.”

Constance pulls in her chin. “I will not. Can’t you see I’m ill?”

“They are waiting.” The nurse’s eyes are hard black stones.

A spike of dread claws at her. “Who?”

“The superintendent and the others. You must go. You can’t stay here.”

Her mouth works but no words come. She begins to tremble. Timothy. He must have received my letter by now. He’ll come. He won’t abandon me like all the rest.

Nurse Hawker sets her shoes on the bed and pulls a wrap from the chair in the corner.

“I can’t go like this. I must pack. I must bathe.”

Hawker’s only reply is to work Constance’s feet into her shoes. Then she’s yanking her from the bed, pulling her to the door like a wayward child. A policeman waits in the hall. He grabs her other arm, and the two force her down the stairs.

It’s all happening too quickly. She must think. She is mistress of this house; they can’t handle her so. But they are down the steps, each turn a dizzying spin, before she can gather words.

A knot of men awaits her at the bottom. Behind them, the servants—the cook, the parlor maid, the butler—are round-eyed and wary. Anne, the children’s nanny, isn’t among them. She stands next to Ingrid, a woman she believed was her truest friend not so long ago.

“What have you done with the children?” she says to no one in particular, her voice raw and tremulous. “I must see them.” I must say goodbye.

No one breathes and then there is movement between the superintendent and Seaver. It’s her mother, pushing her way past them. Her light blond hair has tumbled from its chignon. Her eyes are red welts, her skin so pale Constance can see a blue vein at her temple. Her mother tries to approach her, but the superintendent clamps a hand around her wrist.

“Now, now,” he says, low. “There’ll be none of that.”

Her mother ignores him. “They’ve taken them away, Connie. I’ll get them back. I will see all this put right.”

Constance sinks at the knees like a marionette. The policeman and Nurse Hawker release her, and she is swept from the floor and whisked to the front hall. Her eyes graze the photographs on the table there. The ones of William lie face down. “So the master’s spirit can’t possess those of us left,” Molly, her maid, had said. She wants to scream at the absurdity of it.

Someone opens the front door. A wreath of laurel draped with black crepe hangs upon it, declaring Torrence House a place of death. She’s passing through it when she realizes, looking up, it is Edward Sullivan who carries her. Edward, her brother-in-law, whom she had trusted. Edward, who would have done anything for her weeks ago. She kicks and writhes in his arms. She cannot bear the touch of him.

Then she lurches forward and is sick.

For all the shame of it, it has the desired effect. Edward sets her down abruptly before a waiting carriage, cursing as he looks down the length of himself. When he glances up, his eyes, the same dove gray as William’s, spark with contempt.

Behind him, the others are coming from the house. Her mother shouts from within, throwing insults at the policeman guarding the door. He has barred her from exiting the house. She shifts to French, her curses threading the air with bitterness, lacing it with vitriol.

Constance will not give them a spectacle. With the tip of her shawl, she cleans the front of her dress as Nurse Hawker climbs into the cab. The superintendent approaches, lifting his chin to the vehicle in a signal for her to follow. With the help of his arm, she clambers in, landing in a pile of soiled skirts. Dr. Hendrickson waits inside. The superintendent steps up, and in another minute, they pull away.

At the end of the drive, she turns and looks at the house. It leers back: the stone exterior the color of a corpse gone cold, hooded windows slit into the roof the squint of canny eyes. A swish of the curtains in an upstairs window. Her mother, palms flat against the glass, face white as the moon, watches her go.

She turns her attention to the dark, cold interior of the carriage. Dr. Hendrickson pretends to take an interest out the window.

Panic kindles in her. She’d trusted them, all of them, and they betrayed her. Even William. Especially William. “I…I cannot go to prison.”

Nurse Hawker raises her chin, the accusation in her eyes sharp as a slap. “You should have thought of that before you poisoned your husband.”

Want to keep reading? Buy your copy of The Arsenic Eater's Wife below!

Featured photo: Maria Orlova / Unsplash; other images: Wikimedia Commons, Wikimedia Commons

.png?w=3840)